|

|

A world apart

Wed. 6 Oct. 2004 - Lake Naivasha to the Loita hills, Kenya

Today we drove through several Kenyan towns, including a stop at a curio shop in Narok. I think it's interesting that English is used on most signs, though Swahili is the most commonly spoken language. We stopped for lunch by a dusty roadside, where we made sandwiches on our folding table. We caught the attention of some Masai children, who wandered over for a closer look. Dana, a traveler from Boston, and brought along some bottles of bubbles, which he shared with the children. |

|

|

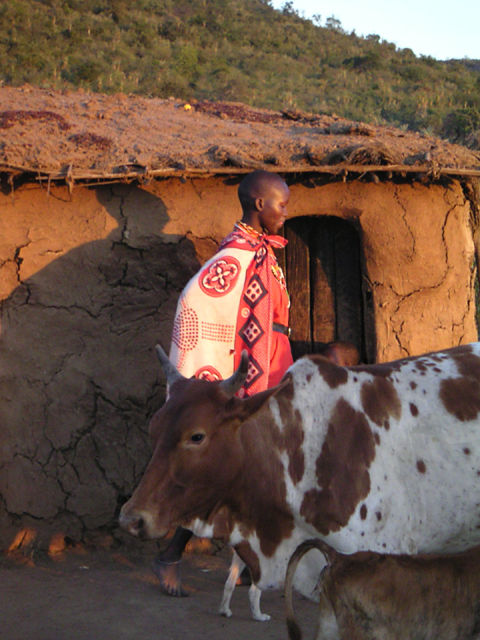

Later in the day, we arrived at a Masai (also spelled Maasai) village in the Loita hills called Inkee (sp.?), where we camped for the night. There are about 70 tribal groups in Kenya (according to my guidebook) but the Masai stand out for their adherance to old traditions. In my mind, I kept comparing them to the Amish in the United States. The tour company, Guerba, pays a group of Masai to let us stay in the village as guests. The villages takes turns hosting the trucks so none of them becomes over-saturated with tourists. The Masai traditionally speak Ma, but some of them attend school and learn English or Swahili as well. Several of the people in this village knew English, including the man who acted as our guide, Josefet (sp.?). The Masai live with no electricity and few possessions. They live off cows, eating beef, and drinking milk and blood. The villages are built in a circle surrounding a cattle pen, a design that keeps the cows safe from predators. The Masai culture is frozen in time, I found myself being increasingly critical as I learned more about it. Most children do not attend school, especially not girls. Men train to be warriors and care for animals. Women build the homes (made from dung and wood) and take care of the homes. Women are bought as wives for the men in exchange for cattle. Against the advice of the government, the Masai practice female genital mutilation and circumsise the boys around age 12 or 14. (Here's a link to a National Geographic article that explains female genital mutilation among the Kenyan Masai.) One boy in the village of Inkee was wearing a New York T-shirt; another one of the boys who spoke English introduced me to him when he found out I was from New York. The shirt had a drawing of the city skyline, and I pointed to the Brooklyn Bridge and said "That's where I live." Josefet told us that the Masai believe all the cattle in the world are a gift to them from their god. Therefore, they have the right to take cows back from other farmers who happen to possess them. Which is to say, the Masai brazenly steal cattle from other farmers. Masai also walk everywhere; they have virtually no carts or wheeled vehicles (though I did see a bicycle in one village later). The Masai in this part of Kenya are known to walk all the way to Nairobi (a seven-day journey) to sell cattle and buy items including clothing and cattle medicine. The Masai have also learned to profit from tourism: charging tourists like us for the opportunity to view their dances, demanding money when people take their pictures, and aggressively hawking souvenirs at the gates of the parks. That night in Inkee, there were no electric lights visible in any direction. Around the campfire, Josefet entertained us with a lecture about the Masai and a funny story about dogs. Oddly enough, I had seen the same story years ago in a scrapbook at a dogsledding lodge in Minnesota. Amazing to hear the same story told in a remote village on the other side of the earth, and a testament to the power of a good story. Josefet also talked about the Masai practice of hunting lions with spears, which the Masai men do (for lack of a better way to say it) to prove their manliness. At night, four of the people on our tour accepted the invitation to spend the night in a Masai hut. (I declined, rememering the unpleasant smell and stuffy air in the hut we toured earlier in the day.) Back in our tented camp, the Masai warriors stayed up around our campfire all night to keep watch for dangerous animals. They had their spears close at hand. If we needed to use the bathroom, they told us, we should flag one of the warriors with our flashlight and get an escort to the toilet. In a short time spent with them, it's hard to know how much of the Masai life is just a schtick for tourists... but in other unprotected camps, like the one in the Serengeti, there was no need for such an armed escort. The Masai life is the simplest human existence. It is also one that, as we would see more clearly in Tanzania, reinforces a culture of poverty and suffering. Masai children are discouraged from attending school and, like the adults, live in dung huts with animals. The Masai believe flies are good luck, and do not shoo flies off their children. |

|